Tracking Desert Rhinos On Foot In Namibia

By Kate Love

Images by Marcus Westberg

Rhino Tracking in Damaraland

Desert rhino tracking on foot took us deep into the rocky mountains and gravel plains of Damaraland. We were inside the 450,000-hectare Palmwag Concession, where rhinos roam freely across the desert of Namibia. Desert-adapted black rhinos have large home ranges and aren’t easy to find, even for local trackers.

Over the past 30 years, the Save the Rhino Trust (SRT) has protected rhinos in the Kunene and Erongo regions. Some of the trackers used to be poachers, but now protect the animals they once hunted for their horns. Black rhinos are smaller than white rhinos, but are more aggressive and can charge if they feel threatened.

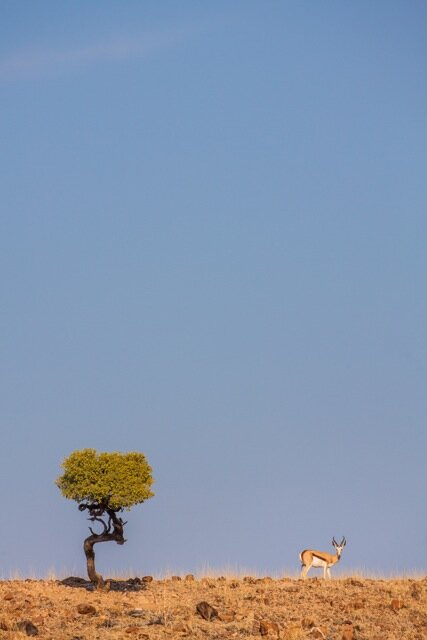

At Desert Rhino Camp, we rose early from our Meru-style safari tent and drove along the rough roads to where the tracking team was waiting. On the way we saw all sorts of arid-adapted wildlife, including gemsbok, kudu, southern giraffe, Hartmann’s mountain zebra and a lone desert elephant near a freshwater spring.

Our rhino tracking safari was led by head ranger Marthin Nuwaseb and his team of four local trackers. The tracking team set out on patrol before sunrise to look for rhinos, a task that can sometimes take all day. Luckily for us, Marthin can read the desert like a map and found fresh rhino spoor near the dried-up Uniab River.

Walking in single file, we followed the rhino tracks along the sandy riverbed, staying as quiet as possible. With the desert sun beating down on our heads, the only sounds were the stones crunching beneath our feet. Some time later, Marthin stopped, put his hand up and waved us forward over the top of a rocky outcrop.

We crouched down low behind some thorny shrubs and peeked over the edge of the steep embankment. Down below was a grassy valley where Unies and her first calf Uoni were browsing on the scattered bushes. Unaware of our approach, they kept moving slowly through the sea of grass swaying in the desert wind.

Desert rhinos have adapted to the harsh desert conditions by drinking less and feeding on plants that are deadly to us, like the Damara milk-bush. Unies is usually solitary, but she will spend at least two years with Uoni before she is weaned, teaching her where to find food and water in this arid environment.

Rain is scarce and desert rhinos are often forced to stray far from water to find desert plants. The trackers had done well to find Unies and Uoni feeding, as later in the day they would probably be resting in the shade. With temperatures ranging from sub-zero to over 40°C, desert rhinos are most active from dusk till dawn.

The trackers know all about Uoni, as they have been closely monitoring her ever since she was born. Uoni was named for the Uniab River and all of the calves share the same first letter as their mother. According to Marthin, we were lucky to find Unies as she is secretive and the trackers don’t often see her on patrol.

Staying upwind, we kept at a distance to avoid disturbing Unies and Uoni while they were feeding. We stayed with the mother rhino and calf for about twenty minutes, losing all track of time in their presence. When the wind changed, Unies detected our scent and disappeared over the hills with Uoni close at her tail.

Alone again in the desert, we walked back along the Uniab River to our waiting open-top safari vehicle. We left the tracking team to continue their patrol, setting off into the open plains to see more desert wildlife. At dusk, we reached the camp just in time to watch the sun set over the flat-topped Etendeka Mountains.

That night, we sat around the fire pit under a blanket of stars, lost for words to describe being so close to a wild rhino. Somewhere out there Unies and Uoni were crossing the desert, unaware of the threat of poachers. Without the local trackers, protecting desert rhinos in the vast plains of Namibia would be even more of a challenge.

Kate was hosted by Wilderness Safaris.

For more information visit Save the Rhino Trust.